Futurepop revisited

I realized this month that it's been 25 years since I started DJing. Possibly down to the month, but I can't quite be sure of that. I DJed in small goth/industrial (what my friends at I Die:You Die call "our thing") nights throughout North Carolina. I started in Greensboro, a night called Celebre Noir. We held it on weekends on the ground floor of a grimy, sleazy club called Dizzy G's. That lasted several years before we moved across town to a strip club which, in retrospect, was clearly a front for drugs and prostitution. We bounced out of there pretty quickly, I moved to Raleigh, and DJed at The Zombie Room at a much better club (King's). By 2007, I fell away entirely except for my sporadic Twitch DJing.

I really liked industrial music. I liked goth, too, but my tastes were far narrower there. And specifically I liked bleeps, bloops, and bass synths. Industrial metal acts were sideshows for me, besides KMFDM (and offshoots like Slick Idiot), and even KMFDM only had like three great albums. But industrial music was it.

I was a punk rock kid who was skeptical of electronic music, but when I was turned on to Nitzer Ebb's That Total Age by a high school classmate, I was hooked. I just sort of hid it from my friends. And then I got into Skinny Puppy. That was basically it. I don't need to repeat the tale here because you can read it elsewhere, but industrial sounded like I felt. Punk rock increasingly didn't by the time I was 16.

Plus I secretly liked to bounce around to the music a little.

So the dominant style of industrial at the time I started DJing, futurepop, fit well with that, and I want to revisit the futurepop years here. It might not even have been industrial at all, depending on who you asked, but that didn't matter. It was club music, made for filling floors. Heavily influenced by eurotrance and synthpop, it was bouncy and melodic. Eventually it got annoying. Every band used the same pre-sets and programs (and in Germany, where there's still a rump scene, they still do). But at the time, it was magic. It was good times, despite the fact that an awful lot of people were irritating and/or self-destructively nuts. The music felt fresh and all our heroes were dead, disbanding, or stuck in a rut. Or all three. Futurepop was uplifting and clubby while still allowing us subcultural freaks to flatter ourselves that we weren't ravers (we were actually ravers). And the music was decidedly uplifting, a stark contrast to the stuff that made me fall in love with industrial but seemed to be needed at the turn of the millenium.

S. Alexander Reed devotes a chapter to futurepop in what is, in my opinion, the definitive critical history of industrial music. He describes futurepop's mood:

Futurepop is about yearning for wonder. Like nearly every previous incarnation of industrial music, it calls for an end to the invisible oppression that radiates from all authority structures. However, instead of invoking the abject sublime to glitch audiences into confronting their own assumptions about reason, power, and propriety, futurepop seeks to give audiences a glimpse of the wondrous sublime entailed bya life free from these quietly tyrannical assumptions. It focuses on that which lies beyond the battle, rather than on the ostensible enemy. It is victory, not vengeance.

Or so goes one line of thinking.

Despite—or more likely, because of—futurepop’s sudden and visible popularity within the global industrial scene, it was subject to harsh criticism in the early and mid-2000s. A musician in the subgenre himself, Tom Shear of U.S.-based act Assemblage 23 is quick to categorize it as “mostly people who can't sing, over 90s-era trance patches.” But criticisms of musicians’ ability and genre borrowings mostly served to mask a deeper suspicion about futurepop. Its preponderance of melody and its avoidance of the abject both painted the subgenre's unspeakable wondrous sublime as awfully Christian. Indeed, early interviewers of Stephan Groth frequently probed him about his Christianity, and VNV Nation does little to shake the question when in the single “Genesis” they declare, “With you I stand in hope that God will save us from ourselves.”

Whether futurepop is actually Christian rock (I don't think it is) or is relying on on Christian themes as a means of speaking to common aspirations and anxieties (probably) isn't much more than an interesting sidenote. What futurepop was was big. Futurepop stalwarts VNV Nation got a hefty writeup in Spin as the next big thing and Apoptygma Berzerk received a Ferry Corsten remix just as Dutch trance was starting to mutate into the all-conquering (and actually terrible) EDM.

A lot of futurepop is not good, but that's not surprising: an awful lot of music is great in the moment but doesn't hold up for more reasons than we can list. And sometimes stuff that wore thin in the past does pretty well on a revisit. So with that in mind, I want to revisit futurepop and see what worked and what didn't.

The Bands That Still Rule

Covenant

Covenant are still one of my favorite bands and are the best of futurepop. A few years ago, I got into a minor Twitter spat with a DJ about whether or not Covenant are/were actually futurepop. It was minor because it was pretty uninteresting, I was on vacation, and trying to set up my first research trip for my dissertation so I don't know where he ended up going. Genre's slippery.

Here's where they're not futurepop: they clearly hark back to older styles of industrial with their relative sonic abrasion and love of repetition. But they're still singing about, as Reed puts it, "the sublime" which typifies futurepop. There's an ambivalent edge to this. Futurepop bands tend to anticipate new communication technologies with both dread and hope. Maybe nobody walks that knife's edge better than Covenant.

In Covenant's Dead Stars, Eskil Simonsson sings, with an eerie prescience, about the soon to be parasocial, surveilled, perpetual now of fame in the digital age:

I touch their hearts

And they touch my skin

I'm on your screen

And you are just so wide

Put us on display

For everyone to see

We write the words

For all to understand

Covenant repeated some core themes over their career. The symbolic power of light in its capacity to banish darkness. The joys of life preceding death. The dull hope of Nordic social democracy. Trains, lightbringers, existentialism, and machines keep popping up.

My very estranged mother died last year. Fitting our ambiguous relationship, my feelings were ambiguous until Rising Sun came up on a playlist. The chorus repeated in my car:

My eyes grow darker

Guide me now

Can barely see your face

Just lead the way

Nothing was ambiguous after that. I wept.

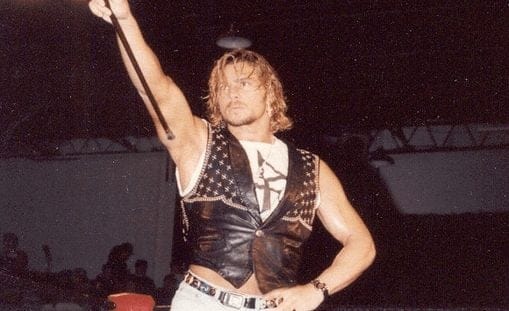

Apoptygma Berzerk

I have a chat with some male friends. We all love industrial music, half of us are dads, all of us are doughy middle aged guys. It's called Husky Boys EBM Chat. They're going to hate my inclusion of Apop here. And I get it, because a lot of their catalog is middling and they suck once they decided to make punk infused synthpop. But their 2000 album, Welcome to Earth, is a futurepop masterpiece.

They're songs about aliens, the internet, and that particular mixture of hope/dread this distinctly millenarian genre obsesses over. Media just before and right at the turn of the millenium is rife with it, and Apop puts it to good use. The album also tosses in a couple songs about breakups which rival Trent Reznor for barely disguised resentfulness. Those don't hold up.

It's also pretty much just a trance album. But what a trance album.

I'll break the chains, I'm out of line

I'm living on my nerve, last days of ninety-nine

Nightmare, conspiracy, depression and lunacy

I need to feel, walled up inside

Locked up, messed up, maybe there is no tomorrow

All this thinking does me no good

I'll miss you my love, but it's about time that this world goes up in flames

Break the chains. Everything before sucked. Let it go up in flames. Let's see what happens.

Wolfsheim

Wolfsheim isn't futurepop. It's synthpop. But genre's slippery and it was in rotation so it's futurepop. Pretty much.

They'd already had a long career prior to the futurepop explosion. Basically, a couple German guys wanted to make schlager tunes, discovered Depeche Mode, and one of them (Peter Heppner) had a magical voice.

Their songs are paint by numbers but somehow transcend the limitations of schlager/synthpop. Beautiful songs about lost youth, magical worlds, and unrequited love (Ich zeige dir mein Angesicht/Doch du siehst mich nicht; I show you my face/But you don't see me):

And two part breakup song epics:

I wish the members of Wolfsheim would stop fighting so we could get a reunion, but Heppner has a solid solo career in Germany and has done some good work with Schiller. It's fine.

Seabound

Headed up by a psychology professor, Seabound dropped languid songs about the ocean and the depths of the human psyche. Those things are also the same thing.

Seabound dipped in and out of view over the decades, presumably because finishing a PhD and being a professor are both a lot of work. But their periodic popping up is always welcome.

Sometimes they got decidedly funky, but it was always with an eye toward more complex arrangements than most of their peers:

The standout to me was always Avalost, about a lost love and the icy shores of Newfoundland. The schlager influence is still here, as it always is with German bands, especially when things slow down.

The Bands That Were Okay But Not As Good As We All Thought They Were and Definitely Not As Good As Covenant

VNV Nation

These were the biggest of the lot. Sustained success (they started doing some sort of quasi-steampunk thing starting in the mid-00s but it was basically the same), huge tours, the aforementioned writeup in Spin. And honestly, they became tedious.

Lyrically, VNV Nation's Ronan Harris is a bit like Bad Religion's Greg Graffin: we all mistook a certain polysyllabic weight for profundity, and yes I recognize the irony of me typing that sentence. But it wasn't really profound, just sort of wishy-washy. Every song was the same: same beat, same synths, same lyrics about a battle for the future.

Not that there weren't moments. The existential musings of Further:

And honestly, earnestly to the point of cheesiness, it's lodged in my memory that Genesis' chorus, referenced by Reed above, was playing in my car on 9/11 when I drove to talk to my family about what the hell just happened. "With you I stand in hope/That God will save us from ourselves". He didn't, of course, but the line at that moment and in that place hit with a certain weight:

As a mark of just how memeable and goofy this all was after about 1.5 albums, VNV Nation became the subject of a wildly popular (within the scene) early meme video made by Bogart Schwadchuck of Episilon Minus (a duo which also gave us Jennifer Parkin, of latter era futurepop project Ayria). Billed as SimRonan, it makes fun of Harris' self-serious repetition, which he did nothing to dispel, according to rumor, by issuing takedown notices for the SimRonan video:

But it's also a testament to their lingering importance and influence that this is the longest entry on this post, despite Covenant being a way better and more interesting band. VNV Nation's also defied the odds by releasing some of their better material relatively recently. When is the Future? is an excellent entry, not least because Harris asks a relevant question instead of insisting on an ambiguous answer:

Icon of Coil

I'm not going to skew this by considering Andy LaPlegua's largely execrable Combichrist project or his love of Confederate flags. Rather, this is/was the club band. They didn't say much, didn't want to say much, and nobody expected them to. And that's fine. Club bangers for a club scene. Mostly everyone got bored of them in my corner of the scene.

But their cover of Pet Shop Boys' New York City Boy is great:

mind.in.a.box

I only somewhat jokingly called mind.in.a.box the band that can save futurepop. What made them notable was that they grooved and had a weird edge a lot of the futurepop scene lacked. But it really only lasted for one album. But what an album:

The Chaff and the Future

Not everything else was chaff, but an awful lot was. I could drop a nearly limitless list of bands and songs. Maybe I'll make a playlist and share it if anyone wants it, but also maybe not. There are/were interesting bands I haven't touched on here.

More interesting is futurepop's afterlife. Really, this was a scene with a limited shelf life, even though it's still technically going (di.fm even has a "Future Synthpop" station). Mostly the bands were at the front of the line for pre-packaged music software like Reason and FruityLoops, and that focus on software over analog synths made most of it sound the same. I knew it wasn't long for this world when a scene friend proudly showed me Reason at his house and the terrible song he made with it, then I started hearing the same presets pop up in floor fillers.

I got bored. The bands got bored. I was convinced powernoise (another post for another day) was going to replace futurepop as the next big thing. It didn't. And I fell away from the scene for a good five years.

Futurepop didn't leave much of a mark. But there are a few interesting bands which carried some of its DNA with them. Young bands, not the 50somethings who lit this briefly burning candle. Body of Light are the most open about these influences:

The prolific Zanias, who's one of my favorite current acts, has moved in this direction and away from her earlier work, which contains more traditional EBM and techno influences. I'm not sure it's accurate to say she just does futurepop now (her interests are too varied) but it's also not accurate to say she's not doing futurepop:

Finally, TR/ST switched from the weird synthpop of his first album to an unambiguously futurepop sound. Predictable? Probably. Does it hit the heights of his first two albums coming out of the then-thriving Montreal electronic/bedroom pop scene of the early 10s? No. Still thoroughly solid? Yep:

In the end, futurepop burned bright and hot, then dissipated. What's lingered is the stench of earnestness, which seems unfair to hate. Maybe even more unfair is to point out that so many of the bands just disappeared or sucked in retrospect, because most bands of any genre both disappear and suck. So maybe a little critical reassessment is due, especially because those of us who lived it are too old to worry about being cool anymore.