Johnny Silverhand and the End of History

I'm doing a second playthrough of Cyberpunk 2077. I beat it when it came out and found it engaging even with its buggy release, but I never got around to doing its Idris Elba saturated DLC.

I was taken by a short side quest this go round which I'd either skipped entirely or glossed over my first playthrough, called The Ballad of Buck Ravers. In it, Keanu Reeves' Johnny Silverhand, the digital ghost of a long dead rock n roll star turned anti-corporate terrorist, listens to a man playing guitar before wistfully recalling his glory days. Johnny asks you to go to a nearby club, The Rainbow Cadenza, to see if any bootlegs of his band are still there. Only the club is now a low end restaurant and the bootlegs are in the hands of a High Fidelty-esque, old time hipster hawking his musical wares out front.

The quest ends with you getting the bootleg for Johnny, whereupon he simultaneously laments and scoffs at the world of 50 years prior:

JOHNNY: Blew 'Saka Tower to smithereens and it's still standing there just the same. Don't want people getting stuck in a rut stuck in the past. Want them to change. Them, and the world.

V: It's been sixty years. Something must have changed.

JOHNNY: Know what changed? The damn facade. Fresh interface plugs, new high fructose syrup and fun fruity flavors. A new face of Arasaka. Same old shit, different packaging... Sure, now almost nobody remembers when a person wasn't just a meat bag full of second-hand implants

You're not supposed to sympathize with Johnny entirely , but I also don't think this is about Johnny. If it were, it wouldn't be interesting. I think it's about Keanu Reeves as the Last Man Standing from the 90s, about Mike Pondsmith and the RPG scene of that same decade, and about how thoroughly everyone thought the terrain of culture had been won.

I'm not a huge fan of R. Talsorian's TTRPGs and that dates back to their early days. They're not bad; they're just not terribly adventurous. Cyberpunk is a pretty rote pastiche of various cyberpunk (the genre) tropes cobbled together in sometimes interesting, usually staid ways; compared with another cyberpunk game, like The Sprawl, and it becomes pretty standard fare and a product of its time. Same with Mekton, the company's mecha game. The writing has a certain nerdy didacticism running through it, which, again, doesn't so much ruin things as annoy me.

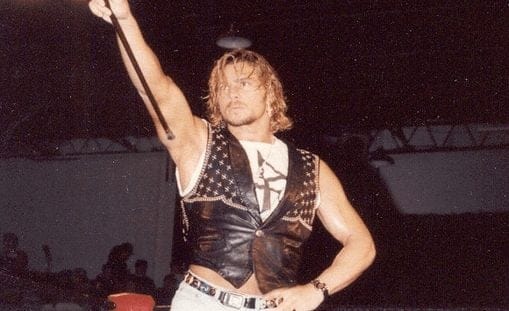

What is interesting is that Johnny Silverhand has been a constant, from the first edition right through to the Cyberpunk Red release in 2020 (roughly coinciding with the video game). Johnny is half cipher/half self-insert for R. Talsorian mastermind, Mike Pondsmith (and, yes, he has an actual self-insert in Maximum Mike, a radio DJ). Pondsmith's use of Johnny Silverhand bears a resemblance to Anne Rice's Lestat: self-insert rock stars who drip damaged cool but pre-dateg and anticipate a specific flavor of 90s cool which neither writer, not being lyricists or seers, was talented enough to make actually cool. Or, to put it another way, both Pondsmith and Rice wanted to create a hybrid of Cobain, Staley, and Reznor but those cool rock guys weren't around yet, and they still lived in the era of hair metal and Boston rereleases. Their characters reflect that lack of knowledge, which was not their fault, by making rock star characters who seemed to fit in less and less the more they wrote about them.

It makes sense that Johnny Silverhand would be a major presence in Cyberpunk 2077, only all the cultural stuff which was the future is now the past. He's stuck there, unable to let go, dispondent that nothing changed, that nobody picked up the mantle after his death. He doesn't want to be remembered, he can't stand not being remembered, and all he has is this one old guy selling Johnny Silverhand merch 50 years after he died. There's a reason Johnny is both a rock star and a political terrorist: the war happened on multiple fronts.

Johnny becomes the stand-in for us, or at least those of us of a certain age. What Johnny delivers in this sidequest is the Gen X lament: it felt as though the terrain of culture, where the most important war was being fought, had been won. It hadn't, and a lot of that feeling wasn't grounded in fact. But the collective feeling remained, the sense that corporate music had been tamed even if hadn't been vanquished, that cool, weird stuff on television and in movies were the new mode, and that the old was on its way out.

I think that whoever cast Reeves as Johnny thought they were doing it because of his long history with cyberpunk and adjacent media: The Matrix and Johnny Mnemonic. But I don't think that's what actually happened. He's representative of a Gen X archetype and that's his appeal for the role. If Johnny is a stand-in for an entire (dead) worldview which has curdled into Brexit and MAGA, Reeves makes perfect sense. Not because he's curdled like so many of his generational cohort (he hasn't), but because he's one of the few left standing as remotely relevant. They cast him because he is the Gen X man, the last of the modernists. His wooden delivery, which usually drives me nuts, works perfectly here: he's just Keanu Reeves, delivering lines in the same flat, world-weary tone he always does, except the man/ghost speaking them is dead. His whole world is dead and he can't move on.

Without checking, I suspect that the Cyberpunk 2077 lead writers and designers are, broadly, of the Xennial cohort or a touch older. They're filling out this world and Johnny's lines. They have the same lament Johnny does: it felt like we struggled so hard just to end up here? It's a loop, haunted (Johnny's a ghost and this is a ghost story, in the end), unable to let go, unwilling to move on. Or, I think an entire collective psychology in microcosm is contained in this scant 10 minutes of gameplay and dialogue. What is Johnny saying here except that all he wanted was a world which didn't sell out? Isn't that what any of us wanted? What I wanted?

In similar ways, R. Talsorian was one of the earliest successful "indie" TTRPG studios. While mechanically it didn't launch a revolution, as a small can-do studio led by a Black man, keeping the lights on, achieving a steady level of success over decades, it's an inspiration and pre-dates numerous other, similar studios. R. Talsorian didn't sell out. Now? It's mostly just Wizards of the Coast and D&D, with almost everyone else barely keeping the lights on.

Music, games, movies, everything in culture seems to hang by a thread. Zero interest rates didn't save anything but the tech companies who turned your delivery apps into a spying regime. Pondsmith as Johnny as CD Project Red as me as you asks, "This is the best we could do?"

In my cultural studies class, I assign two pieces by Jeremy Gilbert to provide insight into the current moment: one on "centrist dads" fleeing Labour in 2019 and his article on what he calls "disaffected consent". In both cases, Gilbert sets up the 2008 financial crisis as the point of rupture where nothing could ever go back, leading to a restive populace in search of something to break free of a system which had seized up. Nostalgia and confusion settled in, not least because of the unmooring realization that some things were better and that those things were sacrificed to a system which also bribed everyone: I'm 50, things are bleak, Cobain and Tupac aren't walking through that door, but I own a house and I have some slightly more expensive food and, oh, a Kevin Smith movie is streaming on demand I haven't seen that in 25 years let's pop some corn.

It wasn't the best we could do and time only moves one way. We age. We die. History moves on, it never ends. Our names, even our deeds and songs, are forgotten. All those moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain.