Recovering the human

One of my tertiary hobby horses is the way academic discourses filter down into broader public discourse as commonsense in winnowed form (and I'm going to somewhat ironically conclude this piece by doing just that). Psychiatric terms being used to pathologize perfectly ordinary unhappiness on social media is a low hanging example. The broader left often ends up in a cul-de-sac, in my mind, via Foucault, unwilling to exercise power but getting really into resistance as a catch all category for good things. That's how things like DoorDash make total sense as a basic right but wielding state power to create a federal Super Meals on Wheels seems impossible or unseemly. You can use the market to resist categorization and state power, see?

But nobody's internalized the commonsense of colloquial postmodernism and transhumanism like the American right.

In a dissected and maligned interview with Ross Douthat over the summer, Peter Thiel stumbles over the simple question of whether he thinks humanity should survive:

Douthat: But the world of A.I. is clearly filled with people who, at the very least, seem to have a more utopian, transformative — whatever word you want to call it — view of the technology than you’re expressing here. And you mentioned earlier the idea that the modern world used to promise radical life extension and doesn’t anymore. It seems very clear to me that a number of people deeply involved in artificial intelligence see it as a mechanism for transhumanism — for transcendence of our mortal flesh — and either some kind of creation of a successor species or some kind of merger of mind and machine.Do you think that’s all irrelevant fantasy? Or do you think it’s just hype? Do you think people are raising money by pretending that we’re going to build a machine god? Is it hype? Is it delusion? Is it something you worry about?

Thiel: Um, yeah.

Douthat: I think you would prefer the human race to endure, right?

Thiel: Uh ——

Douthat: You’re hesitating.

Thiel: Well, I don’t know. I would — I would ——

Douthat: This is a long hesitation!

Thiel: There’s so many questions implicit in this.

Douthat: Should the human race survive?

Thiel: Yes.

Douthat: OK.

Thiel goes on to make a garbled critique of transgender people via posthumanism, ultimately landing on the strange idea that religion and god offer the way to a real transhumanism. That seemed to be where a lot of the analysis focused: the pause, the shift to trangender rights as an incomplete transhumanism. Which is true, but I read the pause on whether humanity should survive as his not knowing what humanity is.

If you read longtermist rantings even a little, it becomes quite apparent that the question of what humanity's longterm survival is wrapped up in the notion that "humanity" is really just a hodgepodge of knowledge, media effects, cultural artifacts, and machines. That is, Thiel's pause was because he was desperately trying to compute a way out of a trap because he doesn't believe in humans but in humans as assemblage of that other stuff.

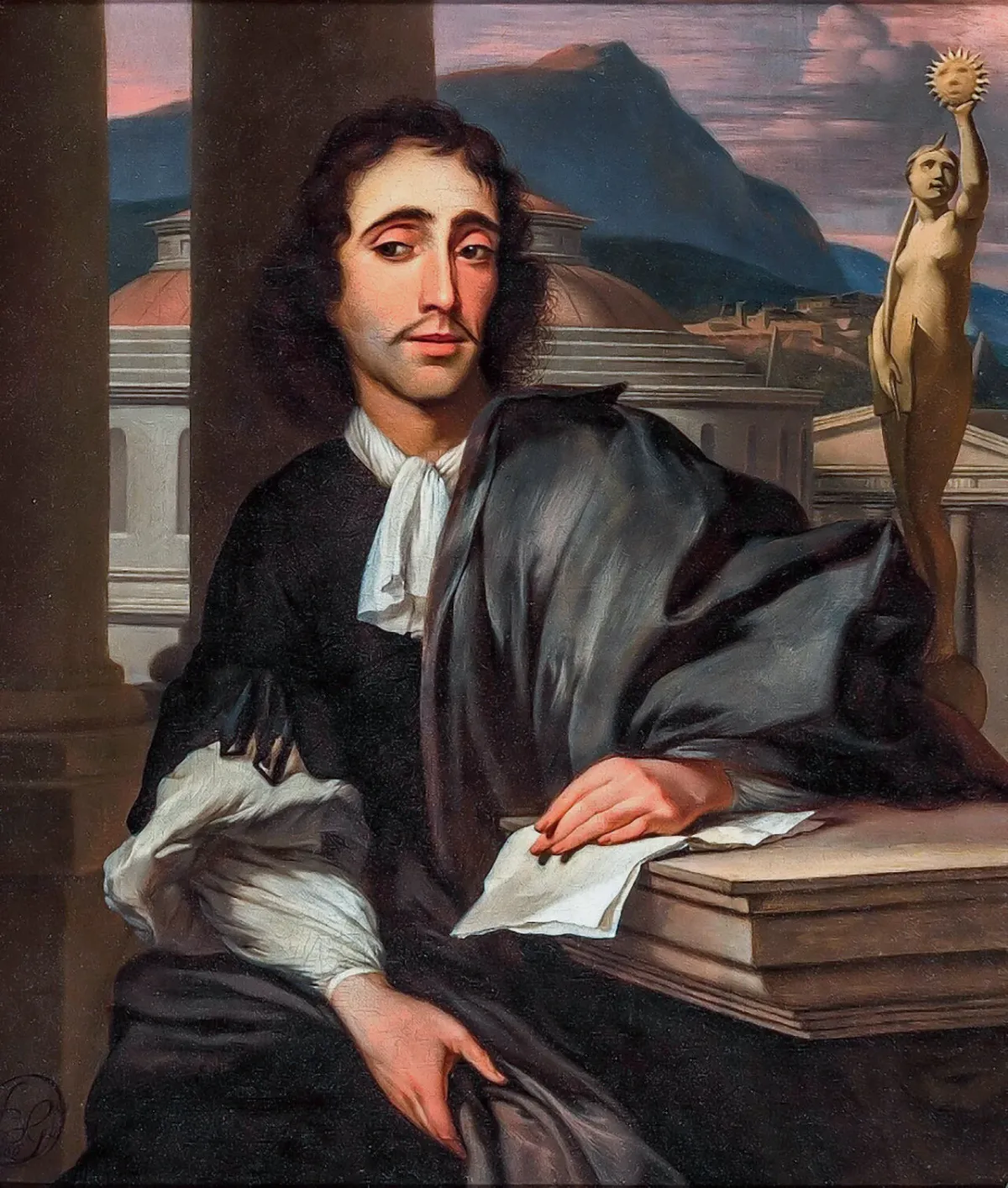

And that derives from a host of really useful post/trans/antihumanist philosophy which filters down into the realm of the popular. Thiel is rather famously a reader of Girard, but I suspect most of the longtermists don't read at all, instead relying on the popularly received understandings of really complex stuff zipping around the zeitgeist. There's a dash of Foucauldian discourse in the longtermist view, a dab of object oriented ontology, a splash of cyborg theory. Because the thing is that nobody really believes in humanity as an important category anymore. Maybe we never have. Plato and Diogenes were arguing about plucked chickens 2500 years ago, which set the stage for the great negation: anytime someone defines a human, there's a counter which shows that something which is clearly human doesn't count as human (women, non-whites, the disabled, etc.). And they're right, in which case maybe the concept of the human isn't very important at all.

I am a humanist. I can't always defend it on its merits. And I still am, in dogged, ragged, unfashionable fashion. And at least some people who stumble upon this are going to think I'm incredibly stupid.

Mostly this is a practical stance. I've seen the posthumanist world and I don't like it very much and I'd venture that most people who aren't me don't like it very much, either. It seems that the deserved grappling with the complicated (being charitable) legacy of humanism, with its rise from an early modern dialectic which constituted the human via its comparison to the non-humans populating non-European continents, settled into a rubric where human was jettisoned as something worth preserving at all.

All the distinctly 2025 ills of the world seem to arise from thinking that humanity isn't really about humans at all. The great negation. If it can't be this category of things, well, it can really be anything. So you can save humanity from climate change by letting 7 billion people die in fits and starts but juicing AI to spit out garbled versions of "knowledge". Because knowledge is really humanity.

And would you really want this? The default mode of being for humans seems to be some varying degree of psychic pain, which is a pretty Catholic thing for a lifelong atheist to say, but here we are. We all hate it, but you can smooth that over by turning it all over to apps, algorithms, and the DSM-5. You can even turn the pain of thinking at all over to AI. And if there is one guaranteed aspect of being human, it's that you will die, except the weirdos who definitely hate humanity the most, the tech-right, are trying as hard as they can to get rid of that, too.

I worry a lot. Liam Kofi Bright is one of the best writers going and I think he's probably correct that you can't really purge the core tension within liberalism (as based on Enlightenment humanistic values): that the debate about who counts as a person, with the understanding that some people won't, is a load bearing idea.

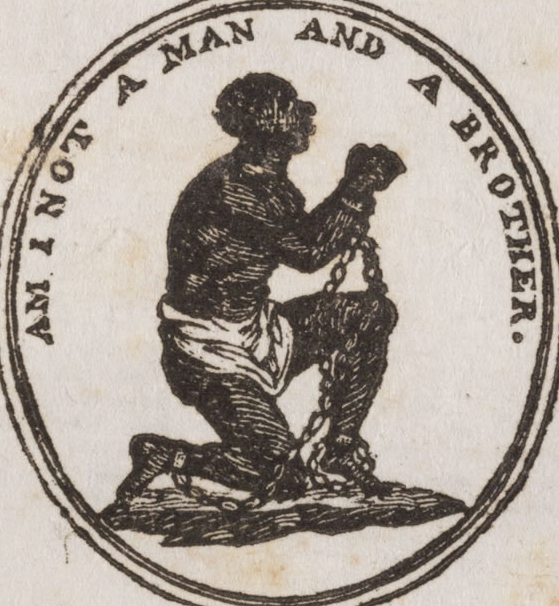

Mostly, then, I think of humanism as a utopian ideal. It's aspirational and I find its most aspirational articulations from people who aren't academics, philosophers, or politicians. And, in a world without any utopias left, that feels mostly okay to me. I think it's notable that we return to the idea of the human as an aspirational category when we're most under duress. There's a recognition, from Gaza to trans communities to enslaved people in the Americas, that being considered a person, a human, is worth asking for. Because the sin isn't in the idea of a universal humanism, whatever its origins, but in the force behind treating someone as not human.

I was quite taken with this Jacobin piece on right wing postmodernist conspiracy theories. The key takeaway is that even very well-meaning people with decent politics get incredibly weird when they jettison the Enlightenment. It's a world without a utopia. That brings me back to what I said a bit above: we live in non-humanist times and it's not very good. I can't put it more bluntly than to say we're all going to die a lot sooner than we otherwise would if we'd cultivated a little more universality and cherished our fellow humans as humans while expanding the category of human a little more. And in any event, Deleuze's most practical contribution seems to be that he unwittingly taught the Israelis to blow up walls more efficiently.

Ultimately, I settle on something akin to Paul Gilroy's stance, who I read quite a bit of but is much smarter than me. I do like Marx a lot more than he does, though, precisely because of the (imperfectly imagined and executed) strains of humanism contained within. Rendering Gilroy's ideas pretty well, a profile reads:

In sharp contrast, Gilroy wants to reinvigorate an old ideal: humanism. In some scholarly circles, calling oneself a humanist can sound not just antiquated, but suspect. It was, after all, the name of the woolly ideology of equality propagated by Europeans at the height of empire, who spoke of the liberty of man while denying it to millions. But to Gilroy, there is hope in the promise of a radical humanism, illuminating a post-racial world. This, he believes, is the humanism of figures who regularly appear in his work such as Du Bois, Primo Levi, Toni Morrison and the French-Martinican revolutionary Frantz Fanon. If thinkers who had lived through the 20th century’s abominations could hold on to the idea of a humanism worthy of the name, then so can we.

And listen, I'm a 48 year old white guy and I don't think it's precisely my place to call for post-racialism or intervene in debates about Afropessimism. But I do like my utopias and I can speak up for them. Are we just numbers and neurons firing? Are we just categories? Or is that imposed upon us?

I don't know. I'd like to hope we're not just those things and I at least pretend that we're not. On my best days I insist that we're not.

I use this quote by Jonathan Beller often, from The Cinematic Mode of Production: Attention Economy and the Society of the Spectacle, at least in part because I get incredibly annoyed at regimes of quantifaction which render every single one of us to a thing. Or, to put it another way, I'm congenitally skeptical of powerful people with a lot of money telling me something, and they're all telling me that humans are just a bunch of electrical impulses and numbers:

And these divergent vectors can be extruded not only along a particular square inch of flesh or in relation to a single phrase or still image, but also across a broader range of these types of texts, which despite their grammatological programs and intentions and their statistical calibrations, are everywhere open to variance, aberration, differance. And while we know that variation is everywhere open to further statistical analysis and data crunching of all types via flowcharts, algorithms, and electronic machines, we also believe (those of us who have ever been a statistic of any kind) that after all the expropriation, deconstruction, and slaughter there is a certain excess there, a voice, a thought, an experience, a will, or a spirit, that does not resolve itself in the mathematical of the now. Isn’t there a leftover presence, a haunting, that is mathematically, linguistically, visually, and politically irresolvable? And who is that? A mere ideological after-effect, a protesting ghost, a reason to write or speak?

Isn't there a ghost there, in you, in us, that we can't pin to the wall?

I hope so.

Addendum: I meant to add this but forgot. One of the ways you can square Thiel's apparent religiosity with transhumanism is to read it as Christianity as transhumanist: you eliminate all the messy anxiety and pain of being human via transcendence. God becomes just another app for assuaging all of that messiness. And then that's just a little leap to the strange religiosity of longtermists and AI obsessives. You can build god. God is machine, machine is god, cyborg is perfection. And, well, money is god, too.

This is all heresy, of course.